Richard Gransden was Christened on the 20th of January 1720 at St Mary Magdelene Church in Cobham. Richard’s birth was one of two records for this family that were extremely hard to locate. Due to the poor quality of the records the details of Richard’s birth had been missed along with his marriage to his wife Mary. This meant that for a long time the search for the Gransden ancestors stalled with this couple.1

Cobham is a small town in the Medway area of Kent about 3km away from Meopham where the early Gransden generations for this family lived at least back until the late 1500’s. Cobham is a village that is surrounded by agricultural land and had a collection of relatively isolated farmhouses and some larger residences that date back to the 16th and 17th Centuries. Cobham was not mentioned in the Domesday Book so the earliest mention of it is of its Church in the Chrism List (list of confirmations in a church) of 1115 which is a copy of an older list. After the thirteenth century Cobham becomes linked to the great families of the area. During the time that the Gransden’s were living in the village of Cobham the Earls of Darnley had not long been the great family of the area having come into possession of Cobham House in 1725.2.

The Earls of Darnely, family name Bligh, came from the Cornwall and Devon area’s. The family was a family of moderate means who had a relatively small holdings in these area’s. One family member John Bligh took up a position in the Company of Salters in London. The Worshipful Company of Salters is one of the Livery Companies or Guilds.3.

The Guild of Salters traces it roots back to the salt trade of Medieval London and still exists today. Originally the Livery Companies were established to protect the interests of traders. The Company of Salters ranks ninth in the order of precedence for the Livery Companies.4. John later became involved in acquiring forfeited Estates in Ireland. The forfeiture of these estates was a way of applying penalties on those who were Irish and had taken part in the Civil War as Catholics in support of the King.5.

Using the lands that John had acquired and building upon them John’s son Thomas enlarged his holding and married Elizabeth Napier whose family had a claim to the Dukedom of Lennox. Thomas’ son John was created Baron Clifton of Rathmore in 1721, Viscount of Darnley in 1723 and finally awarded the Earldom of Darnley in 1725. John also married Theodosia Hyde in 1713, the sole heir of Edward Earl of Clarendon and of Catherine O’Brien, only daughter and heir of Lady Catherine Stuart who was the sister of Charles, Duke of Lennox. It was through this marriage that the the Bligh family eventually obtained the ownership of Cobham Hall.6.

Richard Gransden and Mary Summers were married in a Fleet wedding on the 1st of April 1751. The streets surrounding the Fleet prison were outside the jurisdiction of the Church in the 1700’s. This meant that a legal marriage could be performed without the calling for banns or the need for a marriage license. The calling of banns was the public announcement of a pending marriage for three successive Sundays before a wedding could take place. Clandestine marriages may have been desired for all sorts of reasons for example if the parents of the couple did not agree to the marriage, if there was already an existing marriage or if a couple needed to marry quickly due to a pregnancy. A couple needed a license if they wanted to marry without calling banns. Getting a license was an expensive alternative to calling banns so many couples who wanted to marry without having to call banns for some reason would often opt for a Fleet marriage.7.

Fleet marriages originated in the early days of the seventeenth century. The Fleet was a prison with prisoners able to roam around the streets of the Fleet. This resulted in people of all professions living and working in the area of the Fleet so as to earn their keep and their Liberty. This meant that there were always a number of clergymen who were also inmates performing marriage services in the ale houses, taverns and in the Chapel of the Fleet. Because these area’s were outside of the jurisdiction of the Church the clergymen did not have to read banns or require a license as the marriages still fell within the laws of England but they did not break the laws of the Church.8.

Why Richard and Mary decided to have a Fleet-prison marriage is unknown. Mary was pregnant at the time so they may not have wanted to call banns because it would take too long. As it was even with a rush to the alter Richard and Mary’s first child was born barely six months after they were married. At this stage there is no indication of who Mary Summers was and if that was her maiden name or a name from an earlier marriage. There is also no indication of where she was from. In the marriage record Richard’s place of origin is noted as Cobham Kent and his profession is noted as Carpenter, like his father before him. However even though Mary’s place of origin is not noted it is likely that she lived around the Cobham area if the reason for their speedy marriage was due to Mary’s pregnancy thus it is possible that Mary was the child of Henry Summers also of Cobham Kent. If this is the correct Mary then she was around 20 years old when she was married as she was baptised in 1731.

At the time of his marriage Richard Gransden was 31 years old. Like his father before him this age indicates that Richard was likely to have been apprenticed til the age of 24. Like many other craftsmen it is probable that Richard then spent some time establishing himself as a carpenter before he decided to get married. Even then the speed of his marriage may not have been to his choosing. Bastardy was a massive social stigma in the eighteenth century. While women and their illegitimate children would be taken care of in a Parish their life would not be a pleasant one. It would be a life of pauperism and hard work in very poor conditions. In addition to this members of a Parish would be entitled to search out and discover who the father of any illegitimate children was. These fathers would then be expected to pay a maintenance for their illegitimate children. In many cases couples would get married to avoid the poor system once a woman had become pregnant. This would make the marriage between Richard and Mary a logical step once it was found that Mary was pregnant.9.

Similar to his father before him there is so far no record of Richard Gransden being a member of the Company of Carpenters a Guild for Carpenters that was particularly powerful in London. However it would have been unusual for Richard to not know about the Company even if he was not a member. One of the benefits that the Company gave members was a pension when they grew old and infirm. This pension was gradually eroded during the eighteenth century until it no longer existed.10. It is possible that this sort of change in charity outgoings from the Company of Carpenters was one of the reasons that Richard Gransden senior was well off enough to have a grave stone when he died yet his son does not seem to have been. At this stage although we have a date of death for Richard Gransden there is no evidence of a head stone in the church where his burial is recorded. As the Company of Carpenters lost its power and influence over the eighteenth century this change in the circumstances of Carpenters both members and non-members became more eviden ant had a number of social consequences including the gradual degredation of the circumstances of many carpenters and other craftsmen.

Richard and Mary Gransden of Cobham had a very large family with at least six of the eight children surviving into adulthood. Their children included Richard (baptised 26th October 1751), Ann (baptised 20th October 1753), Mary (baptised 29th October 1755), William (baptised 4th September 1757), Thomas (baptised 18th November 1759), John (baptised 22nd Jan 1764), Jane (baptised 17th October 1765, the only child with a known birthday, 14th October 1765) and Margaret (baptised 8th November 1767). During the eighteenth century it was common for many generations of the same family to live together. Richard and Mary and their children may well have been living with their Grandparents Richard Senior and Ann Gransden nee Drew until their deaths in 1760 and 1775 respectively. The deaths of these family members during the youth and teenage years of the young Gransden family must have had a significant impact on the family, particularly Ann’s death as the role of carer often fell to older relatives while both parents were young enough to work and contribute to the support of a family in other ways. Even if Mary stayed at home with her increasing family it is likely that her and her children would have had considerable interaction with their Grandparents. As the children of Richard and Mary Gransden grew older many of them married and moved away.

During the late 1700’s and early 1800’s farming in Kent went through some radical changes. New crops were being introduced and some of the older crops no longer had a market. This plus an increase in population meant that the tradition of gavelkind now often meant that land was being divided up into smaller and smaller lots. Previously the death rate for children had been so high that it was unusual for more than one male son to survive until he was an adult. So even though land was split between male heirs it was not that common for land to be split up. Where more than one male child survived infancy and inherited it was common for one child to buy the other out when their father died. By the late 1700’s this was less and less the case. 11.

Other social aspects of Kent’s culture had also changed. During the early part of the 1700’s unmarried men and women would live with a farmer and take part in their daily life. By the last quarter of the 1700’s the divide between land holders and their workers including husbandmen and other small land holders was increasing. This meant that farmers were living in their own grander houses. Farm workers were becoming itinerant and were less likely to have a permanent abode. While these changes were happening at the farming level to all communities crafts people were also finding that life was becoming increasingly difficult. By the late 1700’s wage disputes for Carpenters were occurring and around London there were strikes with people pulling down scaffolding as they tried to seek a wage increase or at the very least trying to obtain concessions that had previously been considered part of their rights as Carpenters, for example the wood from the scafolding that could then be used for their own purposes. By this time even if Carpenters were members of the Company of Carpenters the company was no longer able to protect their member’s rights.12. For a family who had at the very least two generations of Carpenters and was probably in the middle of educating another generation of carpenters these were very difficult times.

While there is no specific evidence that the Gransden children went into the Carpentry trade it is very likely that at least one of them did given that both Richard Gransden and some of his grandchildren were known to be Carpenters. 13.

John, the seventh child, was one of those that married and moved away from Cobham. John married Sarah Wood of Strood on the first of February 1782 by licence. Sarah had grown up in Strood, so it was reasonable when John and Sarah married that John would move to Strood when they started their own family. Strood was a small town only a few miles from Cobham. It was an agricultural area but life was also dominated by the river with fishing and oystering being common professions of the town. In addition to its agricultural and fishing industries Strood had been one of the towns in the area that had a place in the manufacture of Kentish cloth which was centred around Eynsford, Dartford, Strood, Rochester and Maidstone.14.

Image © Copyright David Anstiss and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence. http://familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/File:Strood_St_Nicholas_Kent.jpg

Sarah Wood had grown up and made friends in Strood during her younger years. This can be seen by her name on the marriage certificate of James Grant and Martha Hall when there were married in 1781 just one year before Sarah herself was married in the same church in Strood. It is possible that Strood was where John completed an apprenticeship quite probably in weaving and cloth manufacturing. Doing so may explain why John moved from Cobham to Strood. This move may have been a similar move to the type of move that John’s grandfather probably made, moving to where his apprenticeship took place or after he turned twenty four and finished his apprenticeship moving to wherever the work was. This is particularly possible for a move of such a short nature with Strood and Cobham being so close to each other.

Other social aspects of Kent’s culture had also changed. During the early part of the 1700’s unmarried men and women would live with a farmer and take part in their daily life. By the last quarter of the 1700’s the divide between land holders and their workers including husbandmen was increasing. This meant that farmers were living in their own grander houses. Farm workers were becoming itinerant and were less likely to have a permanent abode.15.

It was common for the river around Strood to flood, one of the very large floods occurred in 1791 around the time that John and his family moved to Portsea. This flood was the largest seen in over 60 years and may well have wiped out the livelihoods of many of the local residents including the Gransden family. It is probable that the changes in social circumstances combined with the flood of 1791 combined to help the Gransden’s decide to move to Hampshire.16.

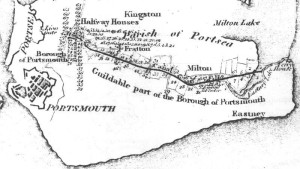

John was the first of the Gransden family to make his way out of Kent. Sometime between 1787 and 1805 John Gransden, his wife Sarah and the first three of their eventual five children, John Robert (baptised 14th September 1783), Sarah (baptised 4th of November 1784) and Robert Wood (baptised 21st of January 1787) moved from Strood, three kilometres away from Cobham, to Portsea, Hampshire. For a family that had mostly lived within 10km of the one area for, at the very least five generations and probably much longer, a move by one part of that family over 160 km was a huge distance. This move is known because of the births of the next two children to this family. Mary Elizabeth Gransden was born on the 23rd of December 1793 and Christened on the 17th of November in 1805 and Charles William Gransden was born on the 5th of March 1797 and was also Christened on the 17th of November in 1805 both were Christened at St. John, Portsea, Hampshire, England. Why there was such a large gap between the birth’s of these children and their Christenings is not known but it may very well have to do with both the turmoil in Kent due to flooding and labour strikes and the move of the family such a large distance from Kent to Hampshire. Another possibility is that John may have had to go ahead of Sarah to find work and a place to live. It is quite possible that this couple were separated for months or even years at a time as they gradually moved their family the long distance to Portsea.

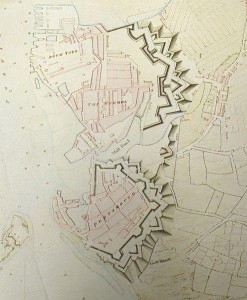

Portsea was dominated by the Navy. During the period from 1770 to 1809 was undergoing major fortification works due to wars with the French. These fortification works and the resultant activity of the Navy caused a huge influx of tradesmen and other groups seeking work during these years. While England was at war with France this activity continued. Once the wars stopped Portsea still supported a large number of tradesmen while ships needed to be repaired. However gradually this level of activity was no longer needed and many tradesmen lost their livelihoods.17. The navy mostly used their own internal workforce and tradesmen so it is possible that John upon moving to Portsmouth joined the Navy or certainly worked for the Navy. This may in explain the curious mixture of tradespeople and navy personnel that his children and grandchildren would later become members of.

Portsea was a town with area’s of extreme poverty. Houses were poorly built and over crowded. The death rate for young children was higher than elsewhere in England and the town had a reputation for being filthy. In addition to the health problems the town was renowned for it pick pockets and for the press gangs that would descend on revellers at the end of the night ostensibly searching for men who were trying to avoid their duty to become seamen. Whilst the results of this may just be an uncomfortable night on a ship before being released if a person had an exemption it may also mean a sudden change in lifestyle and profession for those unfortunate enough to be caught out. Finally there were the hulks off the shore these prison ships would have been a constant reminder to those who lived in the town of what could happen to those convicted of crime.18.

John’s family was not wealthy, or even well off. It is unknown when or where John died but his wife Sarah died on the fifth of January 1846. Sarah had been living for at least five years in the local poor house according to the 1841 census which shows Sarah as a widow and pauper living in the Portsea Poorhouse, Portsea Island, Portsmouth. Sarah was noted as 82 years old at this stage, 1841, and as having been born outside of the Hampshire area. The place of birth was not noted.

Like many before her Sarah probably entered the workhouse because of old age and poverty. This was always an extremely difficult decision for many to make and many would try and live with their families if at all possible rather than enter the workhouse. However in Sarah’s case this was almost certainly not possible. Never wealthy at the best of times by the time Sarah was living in the Poor House her children while not destitute were not well off and were trying had families and responsibilities of their own. It is probable that they could not afford the time, space and expense of looking after their ageing and infirm mother. It is unknown at this stage when John Gransden died but it is quite likely that this event is what caused Sarah to enter the Poor House. Poor Houses in England during the 18th Century were how Britain managed the poor, needy, destitute and ill who were unable to manage for themselves. The origins of Parish Poor, and the responsibilities for the Parish Poor started in Queen Elizabeth’s time when the local Parish became responsible for looking after the Poor. The Poor has been helped by the Parish since before the time of Queen Elizabeth but in 1601 the introduction of the Act for the Relief of poor formalised the process. At first poor relief this was done mainly by hand outs of food and clothing. Eventually it was found easier and cheaper to put all of the poor into one place, the Work House. This became more common during the 17th Century. 19.

The Portsea Workhouses had up to 540 inmates with about 100 of these living at Portsmouth. A description of the daily food from the Portsmouth Workhouses from the 1797 Survey of Poor relief at Portsmouth described the food as;

“Either meat broth or a sort of gruel called flour broth, made of flour and water, is

their common breakfast. Dinner, 3 days in the week, consists of meat, and on the

other 4 days, bread and cheese. Suppers are bread and cheese. Beer is allowed at

bread and cheese meals only. Each adult person has 1 lb. of bread a day, and 8oz.

of meat on meat days.”20

.

When Sarah Gransden first entered the Portsea Workhouse she would first to have had to have gone through an interview so that they Workhouse could establish that she was poor and needed the help of the Workhouse. Sarah may also have had to go to an interview before a panel of the Workhouse Governors to establish her position. This could be an extremely intimidating task particularly for a woman who was undoubtedly old and frail or at the very least suffering considerable hardship. Before Sarah was allowed into the Workhouse proper she may have been separated out to a receiving ward where she would have been checked over for illnesses and if sick she may have been placed in sick ward rather than enter the main part of the Workhouse. Once Sarah was accepted she would have been stripped, washed and be issued with her Workhouse Uniform. Sarah’s own clothes would have been washed with a disinfectant and put away for when she may next be out of the Workhouse. Sarah’s uniform would have been the only belonging that she had and even that was considered to be the property of the Workhouse if she left without permission she may well have been arrested and charged with theft of her uniform.21.

Workhouse, St James’s Parish (Not Portsea but it gives and idea of what a workshouse could be like).

Salteless gruel and dry bread a description of food in a Workhouse. 22.

“We had our breakfast given us, which was exactly a repetition of supper-saltless gruel and dry bread. We ate as much as we could and were very thirsty. I had drunk some water with my hand from the bath-room tap as soon as I got up. We put what bread we could not eat into our pocket as a supply for the day, and were told to empty the rest of our gruel down the w.c. It thus disappeared; but what waste! A mug of coffee or tea would at least have washed down the dry bread; or a quarter of the quantity of gruel, properly made, would have been acceptable, with a mug of cold water for a proper drink.

As we had now no food, were were glad to appropriate the remainder of our workhouse bread, putting it in our pocket. We should have nothing else all day, for the portress told us when we had done our work we might go out at eleven o’clock. We thanked her- we had expected to stay another night, and perhaps pick oakum, but we should have almost starved on the food, as our sugar was in out bundle, so we were relieved to find we had only to clean the tramp ward and go.

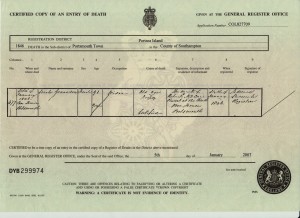

In the Workhouse there were generally two classes of inmates the 1st Class inmates who were the elderly and infirm and the second class inmates who were the able bodied. The aged and infirm had slightly relaxed rules and regulations that they had to abide by. It is probable that Sarah lived her remaining five years at the very least in the Portsea Workhouse she certainly died there. Sarah died of dropsy also known as Congestive Heart Failure. In the 1800’s and earlier Congestive Heart Failure was known as Dropsy or Hydropsy because of the accumulation of fluids in the tissues. It is possible that Sarah already had this condition before she moved into the Workhouse and this could in fact have been part of the reason that she entered the workhouse. The oedema that is caused by Dropsy can result in ulcers and other signs and symptoms of Congestive Heart Failure that would have made it very difficult for an elderly lady to treat herself in a home with little if anything in the way of modern facilities.23.

Sarah’s death certificate claims that she was 91 at the time of her death. This age does not correspond with her birth or the age she gave at the time of the 1841 census. Sarah died on the 5th of January 1846. She was christened in November 1759 making her 87 years old. Whilst not the 91 that she may have claimed it was certainly a respectable age at such a time. It is unknown why Sarah’s age was written as 91 years old but it was a fairly common thing at this stage for the elderly to claim they were even older than they were simply because great age often engendered a certain respect. It is probable that by claiming that she was older than she was Sarah was gaining a respect for her age and wisdom.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

References

1. City Ark Parish Records http://cityark.medway.gov.uk/query/results/

2. Dymond, T. 2008. Cobham. Cobham Parochial Church Council. Cobham and Luddesdowne Church Printing, Cobham-Luddesdowne, Kent, UK.

3. The Bligh Family. Medway Council Kent. http://www.medway.gov.uk/leisureandculture/libraries/archivesandlocalstudies/learningfromarchives/darnleyexhibition/theblighfamily.aspx (Accessed 9th of April 2014)

4. The Salters Company http://www.salters.co.uk/ (Accessed 9th of April 2014)

5. Laws in Ireland for the Suppression of Popery. http://library.law.umn.edu/irishlaw/land.html (Accessed 9th of April 2014)

6. Opcit. The Bligh Family

7. Fleet Prison 2014 http://www.marriagerecords.me.uk/fleet-prison/#.UzleM49Dt0y (Accessed 31st of March 2014)

8. Ibid

9. Old and New Poor Law Records. 2011. Suffolk County Council.

http://www.suffolk.gov.uk/assets/suffolk.gov.uk/Libraries%20and%20Culture/Suffolk%20Record%20Office/2011-09-06%2027%20OLD%20&%20NEW%20POOR%20LAW_B&W.pdf (Accessed 2nd of April 2014)

Nutt, T. 2006. The Child Support Agency and the Old Poor Law. http://www.historyandpolicy.org/papers/policy-paper-47.html (Accessed 3rd of April 2014)

10. Carpenters Company http://www.londonlives.org/static/CarpentersCompany.jsp (Accessed 1st of April 2014)

11. Jessup, F. 1987. A History of Kent. University Printing House, Oxford, UK: 110- 12. Ibid: 110-121

13. Opcit: Carpenters Company

14. Opcit. Jessup, F. 1987: 85

15. Ibid 110-121

16. Historical Weather Events http://booty.org.uk/booty.weather/climate/wxevents.htm (Accessed 3rd of April 2014)

17. Hampshire City Council 2003. Portsmouth and its people 1800-1850 Portsea Island at the turn of the century.

Hantsphere Heritage. http://www.hantsphere.org.uk/ixbin/hixclient.exe?

a=query&p=hants&f=generic_theme.htm&_IXFIRST_=1&_IXMAXHITS_=1&%3dtheme_record_id=hs-hs-portc19c_content1&s=HO49UVNvSx5 (Accessed 9th of April 2014)

18. Ibid

19. Higginbotham, P. 2014 The Poor Laws http://www.workhouses.org.uk/poorlaws/ (Accessed 7th of April 2014)

20. Hgginbotham, P. 2014 Portsea Island and Portsmouth, Hampshire. http://www.workhouses.org.uk/PortseaIsland/ (Accessed 7th April 2014)

21. Higginbotham, P. 2014. Entering and Leaving the Workhouse. http://www.workhouses.org.uk/life/entry.shtml (Accessed 7th of April 2014)

22. Higgs. M, Greenwood, J. and Others. 2013. Tales from the Workhouse. Amazon Digital Services, Inc.

23 Higginbotham, P. 2012. The Workhouse Encyclopedia. The history Press, Stroud Gloucestershire, UK.

DNA evidence from their respective descendants suggests that John GRANSDEN who married Sarah WOOD was unlikely to have been a son of Richard GRANSDEN and Mary SUMMERS. Samples compared came from five descendants of the former and four descendants of the latter couple.

Hi Bernard.

Your comments are interesting. I am currently struggling to identify which line of Gransdens I belong to. How might (your) DNA evidence help me?

Many thanks if you can advise.

Bill