Ghost Town of the Burragorang Valley

By Ray Bean

An article written by Ray Bean sometime in the 1950s. The language and detail are Ray Bean’s. The photos were taken by Ray at the time he wrote the original article. There is some damage to the article, hence the missing words. In some cases, Ray has inserted handwritten words into the original typewritten article. Where I can identify what these words are I have included those words. Where I have not been able to identify the word, I have kept to the typewritten words that Ray used originally.

Yerranderie today, a township of about fifty inhabitants seventy-six miles west of Sydney in the extreme Upper Burragorang valley, rests from the trials of its vigorous past and preserves its picturesque character in rugged scenic beauty.

Once a settlement of two thousand people who lived on the mining of Yerranderies’s rich silver-lead deposits, it sprang into life and grew with dramatic suddenness. Like a bushfire, it flourished briefly and died. The story of so many mining towns.

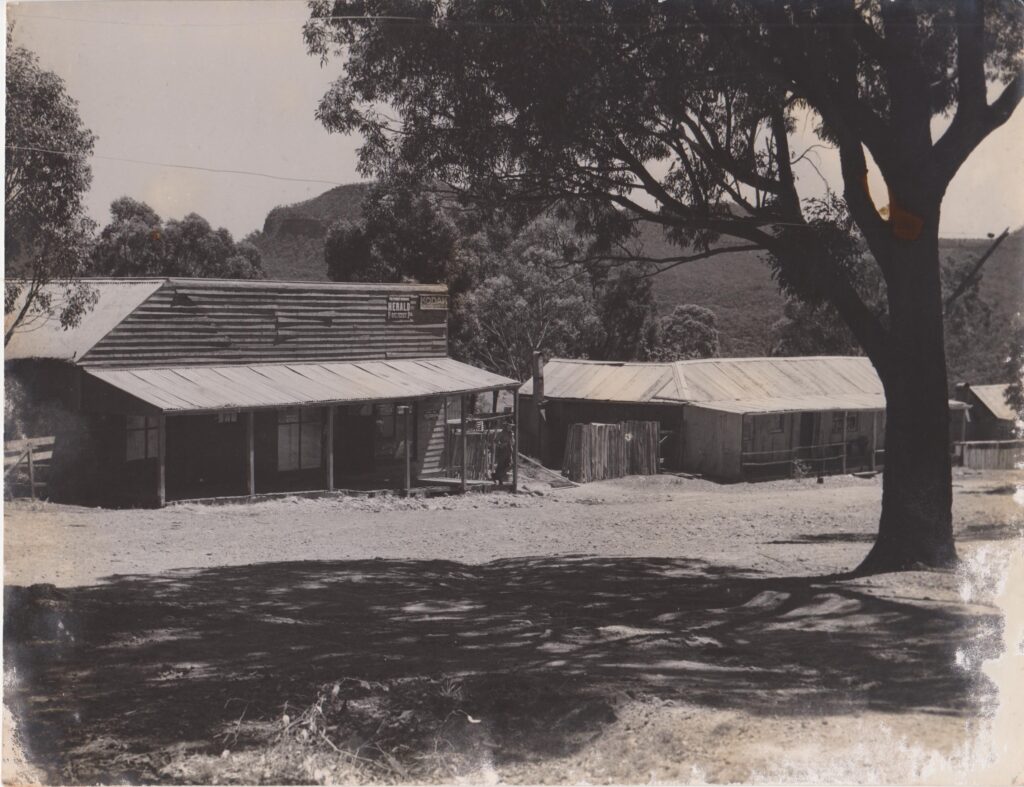

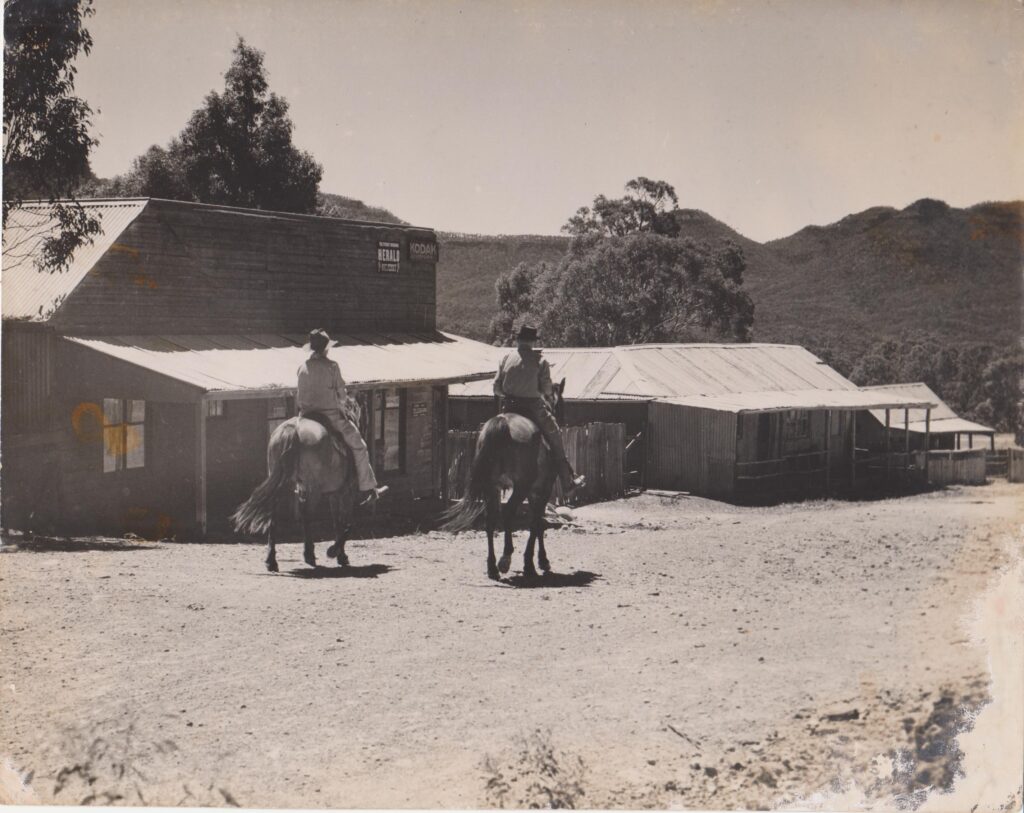

What now remains of the township are enough dwellings to house the fifty or so inhabitants, scattered over the landscape as though from some giant hand, and the main street which to the first glance of the traveller might be the set for a Hollywood-style “Western”, were it not so real.

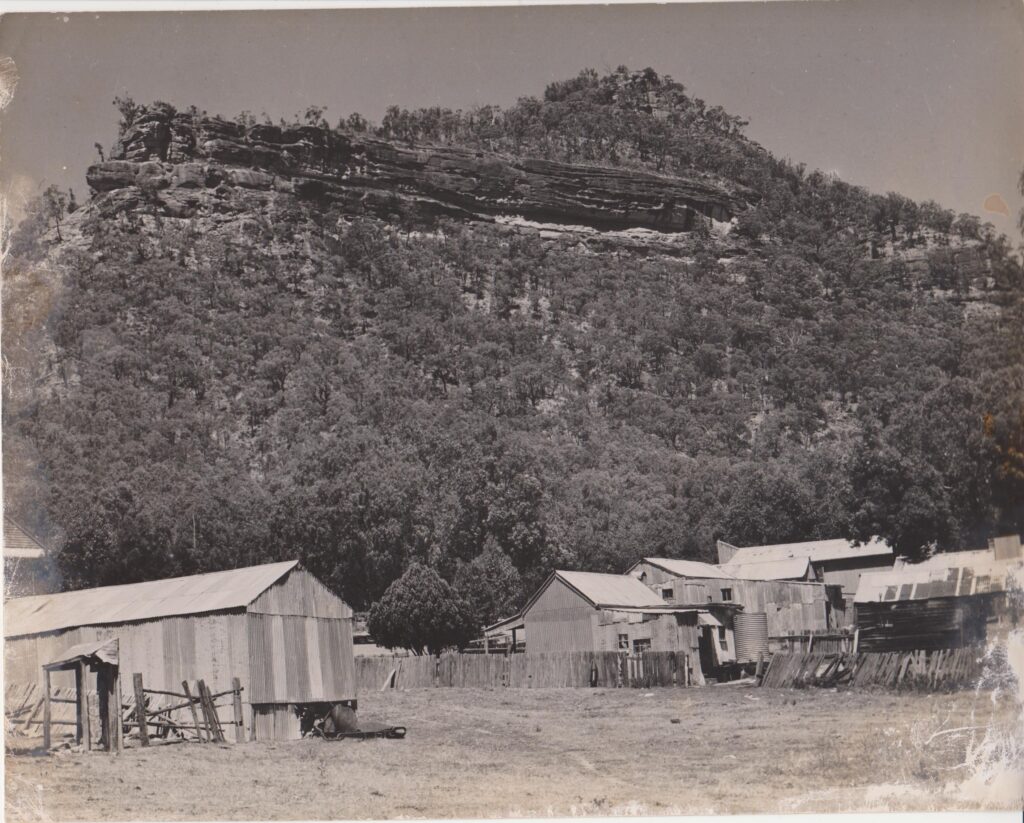

The post office and bank; a two-storey structure, its wood bare of paint, has a row of wooden posts along its front supporting a balcony; the posts rising straight out of the road, there being no footpaths in Yerranderie. Outside under a gum tress is a hitching rail twelve feet long; a relic of past times when business was more brisk.

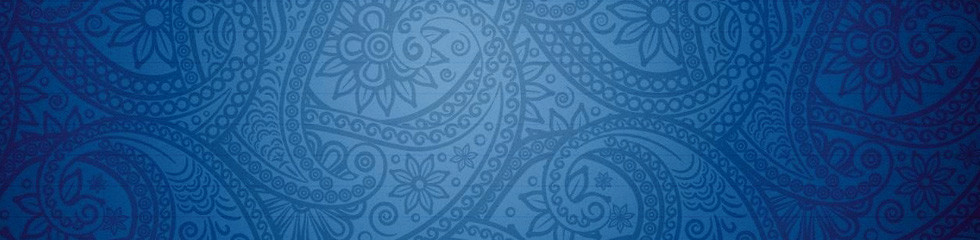

Directly behind the post office Yerranderie Peaks rise; a landmark from which the district takes its name. At one time the town was known as “The Peaks”.

Across the street is the general store; a wooden structure of one storey, but with a false front carried high above the awning, and a boardwalk reminiscent of western American gold rush towns.

The bakery, next door, an odd mixture of similar construction and typical outback Australian architecture, corrugated iron whitewashed; with a few tiny stores scattered along the wide sloping streed dotted with self-sown gum trees make up the main thoroughfare. The “Silver Mines Hotel” is a half mile away from the rest of the town and farthest from the mines, which I thought was designed to remove temptation from the path of the miners during working hours, but nevertheless, very unkind.

These structures have a backdrop of intense beauty. Across the valley are the rugged Tonalli Walls rising to nearly four thousand feet, their sandstone ramparts out by the symmetrical cull of Byrnes Gap, a half-mile wide.

The entire district is a maze of sandstone ridges with basalt **** tops overlying ancient rocks. The vivid transparent mist from which the Blue Mountains take its name softens and enhances the ruggedness.

Standing on the boardwalk and leaning against a verandah post of the general store I was discussing past days with an old-timer who had worked in the mines and had chosen Yerranderie for his retirement because of its isolation, quietness and beautiful setting. Our attention was attracted to some violent activity in the town; two horsemen were cantering up to the post office-bank. They swung simultaneously from their saddles and hitched their horses to the rail.

The old-timer stopped talking and looked out with half-closed eyes through the bright sunlight, getting the horseman into focus. I was fascinated by the scene, and so was my friend apparently, for his gaze took in every detail as he slowly put his pipe in his mouth, took a long draw and exhaled the blue smoke into the sunlight. The horsemen by this time stood at the entrance to the bank, pausing a moment before entering.

“You wouldn’t need much imagination to see them pull their six guns before going in, would ya?” said the old timer, still gazing across the street. You wouldn’t.

There is almost no mining done in Yerranderie now. The mines, “Bartlett’s”, “Bore Block” and “Silver Peaks” have taken on the deserted appearance of all worked-out mines; heaps of mullock of various colours, twisted tramlines and rusted boilers of once busy engines; unbroken tools and a small truck tilted up at the end of its rail jutting into space over the end of a mullock heap. A bushfire at “Bartlett’s” four years ago robbed the scene of the seventy-foot-high timber mind heads. The only other industry is a little saw-milling and farming in the surrounding district.

A twice-daily bus service to Camden has been in operation a year, and so daily mails are received. The arrival of the bus was not the event I expected; the one I saw delivered two newspapers.

At the weekend and holiday times, a great number of bushwalkers arrive laden with heavy rucksacks and briefly the tiny town comes to life.

That is the Yerranderie of today. Between 1880 and 1912 ?******? Of the silver-lead mining, the miners, prospectors and others who hoped to get rich quick poured into the towns from Camden in the only means of public transport; Butler’s coaches, which stopped running there in favour of automobiles about 1920.

So rapid was the towns growth and so rugged the terrain that no time was given to town planning even should someone have had the inclination. One could hardly say Yerranderie was built. A town of ridges and gullies, it rather accumulated around the mines. Every ridge and gully contained cottage or shack.

The extreme high temperatures and dry summers caused the tanks to dry up and the creeks became the sole water supply. The Tonalli River was a particularly suitable place for dwellers and shacks extended far up its banks.

There were no footpaths, and transport being mostly by foot the result was a maze of tracks from shack to school, hotel, store, creek and neighbours shack. A few houses were built near the hotel and so a suburb known as Newtown sprang up.

Much timber was removed for building and propping in the mines and nature retaliated with an abundant growth of saplings which made the township more congested than ever.

The ore concentrates were bagged and transported to Cambed on flat-topped waggons drawn by bullock teams of twenty-two beasts, and later replaced by smaller units of nine to sixteen horses.

The first stage of the trek was Yerranerie to Byrnes Creek; a distance of about eight miles, from where fresh teams hauled the heavy loads over the fertile flats of the Wollondilly River; the sandstone ramparts flanking the valley making a scene which it is doubtful the rough road permitted the traveller to appreciate.

The bullock and horse teams; the stagecoach, have all gone under the marching feet of progress, and soon the road itself will meet the same fate, for the flooding of the Burragorang Valley when the Warragamba Dam is completed will put this road in places under two hundred feet of water.

At the end of the second stage was a depot halfway up Burragorang Pass and another team traversed the final stage across the tableland to the railway at Cambden; a distance of forty miles from Yerranderie.

This read was notoriously rough and the horses pulling the coaches ?****? knew their jobs and the road so well that the polers would lower the wheels ?*****? one at a time into the huge potholes to avoid the sudden lurch of the coach and discomfort of the passengers.

In wet weather the ore waggons bogged in the mud and at a time when bullocks and horses were both in use the story is told of a waggon horse-drawn sinking to the aisles. The teamster built himself a shelter from the rain and camped until a bullock waggon returning empty from Camden came up. The two teamsters set to work and dug the mud away from the front of the waggon making a sloping channel rising to the road level, and then dug away from the back wheels what mud they could, including large rocks floating in it. Harnessing the horse team to the waggon and the bullocks to the horsed the straining increased with the colour of the teamsters’ language. The result was a splintering crash as the accumulated power of horse and bullock pulled the waggon from the mud leaving the lower half of the back wheels embedded and smashed spokes flying in the air. It was also a frequent occurrence under such conditions for a team to pull the pole from a waggon making it more difficult than ever to remove.

Despite the roughness of the roads many empty waggons could be seen bumping their way on the return journey with the teamsters aloft fast asleep, stretched out after their stay in Cambden.

The decline of Yerranderie began about 1912 when the prices of sliver-lead dropped considerably. Some of the miners lured by small finds of gold set out into the mountains to gamble with fortune on the nearby Kowmung River.

The Great War, two years later struck the final blow from which Yerranderie never recovered. The concentrates in those days were not smelted in Australia, but were sent to Germany for treatment.

Attempts to revive the industry after the war appear to have been frustrated by labour difficulties, which seem to always follow in the wake of such catastrophes, and the once thriving township wavered and slowly dwindled like the mist of its surrounding mountains, leaving only a quaint ghost of its former self.