Chelsea Pensions Part 2- William Pratt

Like many other ancestors who have received a pension, I didn’t find out about William Pratt’s pension until I found him in a census. William Pratt was in the 1851 census at the age of 72. In the 1841 census, William had been noted as a labourer. So, it wasn’t until he was living off his pension in his older age that the pension became his sole source of income. This is often the case with those who are on pensions, they are entitled to them from the time that receives their injury but they either don’t receive them or do not use their pension as their sole or major source of income until later in life. This can make finding details of the person’s pension and service harder to find, as there is not necessarily a reason to look for army records until a reference to a pension is found. Another reason for always checking every person in every census that the person and family are likely to be living.

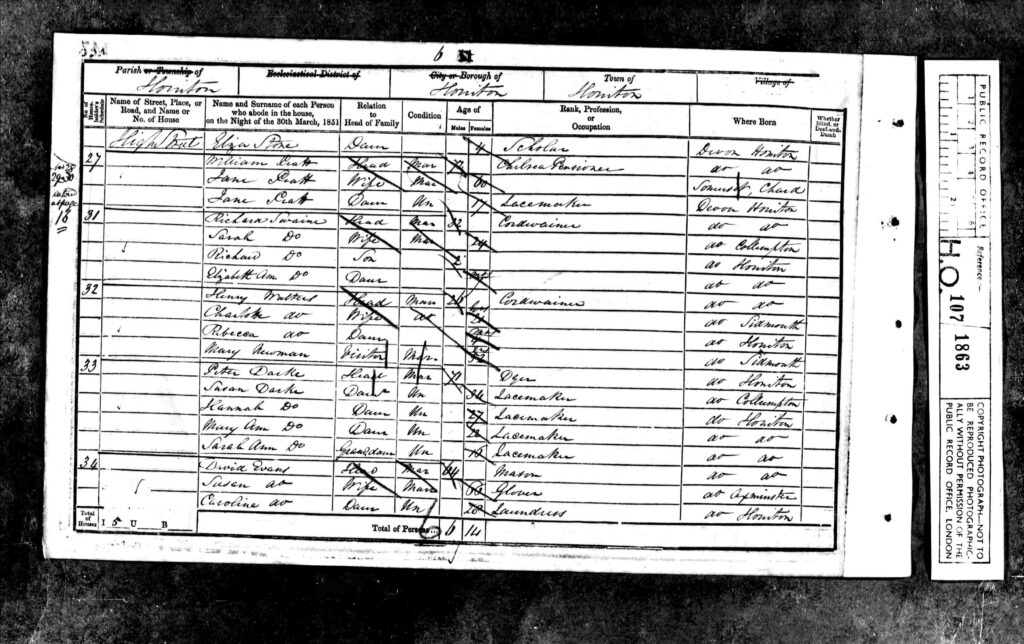

1851 Census- William Pratt, Chelsea Pensioner

Ancestry.com. 1851 England Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005.

Using the Census details for William Pratt, I was able to find his attestation papers. According to William’s attestation papers, he served in the army for over 18 years, from 1803- 1822. Even better, from a genealogy point of view, his papers were able to give me William’s birth parish and a general description of what William was like and why he had left the army. William was pensioned out because he was worn out, his conduct was good, and he had received a slight wound in his right hand and hip at Waterloo on the 16th of June 1815.

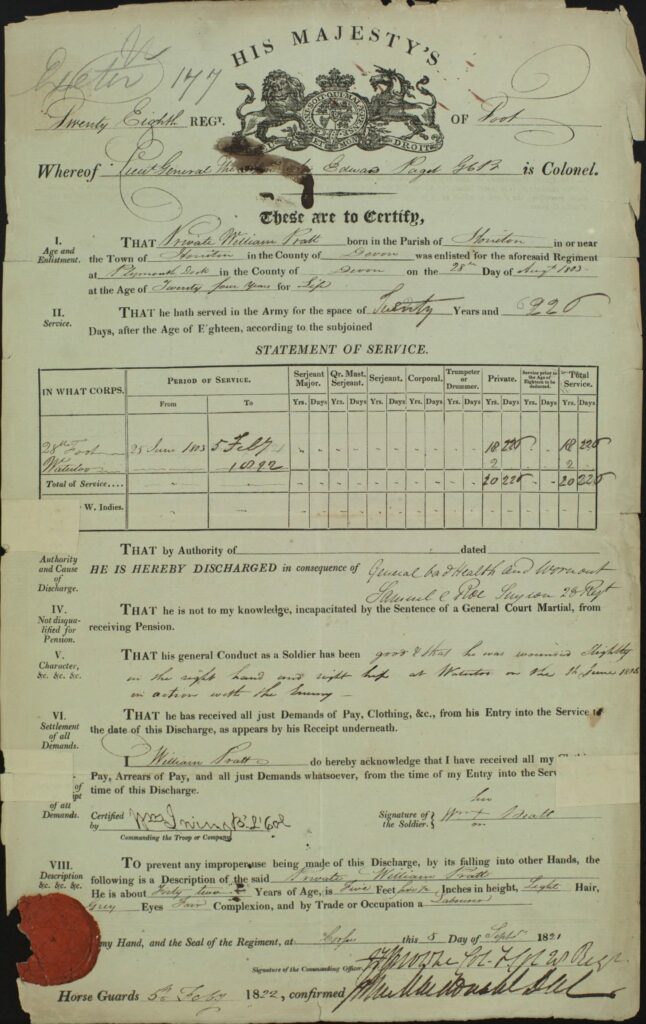

Wo 97 – Chelsea Pensioners British Army Service Records 1760-1913

William Pratt Discharge Records

Based on the information about William that I was given from his attestation papers, which also become his discharge papers, I was able to find out a lot more about William’s life and times in the British army. William had enlisted, or had been pressed at the Plymouth Dock in Devon on the 28th Day of August in 1803. William served for 18 years and 226 days, but, because he had been in the Battle of Waterloo he was attributed an additional two years of service giving him a total of 20+ years of service attributed to him on his service record. This was important because these additional days meant that he could claim a pension. A pension, at this time, could not be claimed unless the solider had served for 21 years. William had served close enough to the 21 years and had been discharged partially due to injury, being worn out, and with a good character. It is probable that he received his pension because he was this close to making the 21 years.

William’s early days in the army would have included his attestation before a magistrate. Once he had completed this William would have belonged to the Army until they discharged him. William would have been paid roughly one shilling a day, hence the saying- the “Kings shilling”. From attestation, William would have then gone through a medical process to see if he was fit for service. He would have then spent some weeks in a depot where he would be kitted-out and trained.

William’s kit would have included his uniform and a backpack. The uniform of the 28th Foot was red, like most of the other uniforms at this time, with yellow facings. The yellow facing was distinct to the 28th Foot only. The uniforms were often tight and uncomfortable for soldiers to wear. This may be why the 28th was used to trial loose grey trousers when on a campaign in 1809.

A Soldier of the 28th Foot in his uniform with the yellow facings.

By Vinkhuijzen, Hendrik Jacobus (1843-1910). Published 1910 according to this NYPL catalog entry and this Google book listing. – From The New York Public Library, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47db-b2a6-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4250304

When discharged William was 42 years of age, five feet, five inches with light hair, grey eye and a fair complexion. His trade before and after being in the army was that of a labourer.

William Pratt fought in the 28th Regiment of Foot, 1st Battalion also known as the North Gloucestershire Regiment. The 28th was particularly active during the Napoleonic Wars. William Pratt joined the Regiment in August of 1803. By 1805 the 1st Battalion was in North Germany and from there were deployed to Copenhagen. They did not arrive on the Peninsula until 1808.

On the Peninsula, the 1st Battalion of the 28th participated Battle of Copenhagen in August of 1807. Next, they were deployed in Portugal in 1808 where they took part in the Battle of Corunna on the 16th of January 1809. They were evacuated from the Peninsula the next day. The Regiment was split at this stage, with some members participating in the Battle of Talavera, the later became the second battalion, and others in the Walcheren Campaign, William stayed in the first battalion so probably saw action at Walcheren.

In 1810 the Battalion saw action in the Battle of Barrosa. Over the next few years, between the Battle of the Barrosa and the Battle of Waterloo the 28th saw action at the Battle of Albuera, the Battle of Arroyos dos Molinos, the Battle of Vitoria, the Battle of the Pyrenees, the Battle of Nivelle, the Battle of Nive, the Battle of Orthez, the Battle of Toulouse and then finally the Battles of Quatre Bras and the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

The 28th Foot at Quatra Bras

By Elizabeth Thompson – Artrenewal.orgNational Gallery of VictoriaFile:Elizabeth Thompson – The 28th Regiment at Quatre Bras – Google Art Project.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4082016

The Battle of Waterloo was the first Battle where all soldiers were entitled to a Medal for their service. Along with many of his comrades, William Pratt received a Medal for his service during the Battle of Waterloo and is noted on the Medal Roll.

The Medal that all soldiers who fought in the Battle of Waterloo were entitled to.

William continued on, after the Battle of Waterloo for another seven years. The 28th served in the Mediterranean, Ireland and then England and finally in Australia. It is possible that hearing stories from members of the 28th later in life contributed to the decision that William’s son made when he chose to move to immigrate to Australia.

I don’t know if William would have seen action in every one of these Battles. It is probable that he would have been involved in most of these battles, if not all of them. No doubt, he occasionally missed out on some due to sickness or because he was on furlough.

During his time in the 28th Foot William and his companions saw parts of England briefly, usually for a short time every year. He may even have had the occasional chance to catch up with his family. However, despite some of the awful conditions that William would have experienced, would have been provided him with travel opportunities and a steady job. It is probable that no other profession could have given him any of the opportunities that the army would have given him. William was able to see parts of Ireland, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Portugal, Spain, France and Belgium as well as parts of England and the Mediterranean that we would have had no chance of seeing had he not taken the Kings shilling.

28th (North Gloucestershire) Regiment of Foot

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/28th_(North_Gloucestershire)_Regiment_of_Foot

Brown, S. British Regiments and the Men Who Led Them 1793-1815: 28th Regiment of Foot

https://www.napoleon-series.org/military-info/organization/Britain/Infantry/Regiments/c_28thFoot.html

(Muster Books and Pay Lists) at The National Archives.

FindMyPast

The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; General Muster Books and Pay Lists; Class: WO 12; Piece: 4430

The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; General Muster Books and Pay Lists; Class: WO 12; Piece: 4430

The National Army Museum. 28th (North Gloucestershire) Regiment of Foot.

https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/28th-north-gloucestershire-regiment-foot

White. Service in the British Army.

https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/blog/2018/03/16/service-in-the-british-army

Pingback: Historical Pensions Part 4 | Gransden Family