Link to Part 2

In 1855 Edwin Gransden arrived in Sydney on the Washington Irving, Captained by Isaac Durant. Durant had only been Captain of the Washington Irving for a short time with a Captain John Jones being the Captain prior to Isaac Durant. Captain John Jones had sailed the Washington Irving to Australia in 1852 via Port Phillip Bay in Victoria.[1]

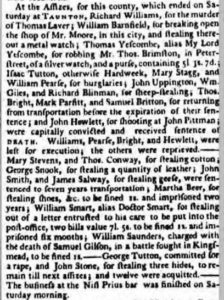

The Washington Irving had originally been built in 1845 for the firm T. Edridge of London. Even though the ownership of the Washington Irving was in London, the actual building of the ship took place in the United States. The Ship was of spruce and during repairs in 1857 was sheathed in felt and yellow metal.[2]

Richard Barnett Spencer (1840 – 1874)

Title Forward Ho: A full-rigged ship off Dover.

Public Domain

Similar Type of Ship to the Washington Irving

In 1855 the Washington Irving arrived in Sydney but the first voyage with the new Captain, Isaac Durant, was had its excitements. As well as the crew, including Edwin Gransden, the Washington Irving carried Dr Manby, the Ships Surgeon Superintendent,[3] as well as 224 immigrants. The immigrants included 134 adults and 74 children between the ages of 1 and 14 years. The trip took 90 days and despite the work of the Surgeon Superintendent there were two deaths, one a 74 year old man and one a younger person dying of Scarlet Fever. However, to balance the deaths there were also three births.[4]

On the trip out to Sydney the Washington Irving first met bad weather for three weeks with heavy gales[5] and then came across icebergs on the first and second of March 1855.[6] One of the passengers, R. W. Farmer, writing to the Editor of the Sydney Morning Herald described the events.

“about 11 o’clock, steering S.E., wind fresh, we were passed on either side by a large iceberg rapidly followed by others until about 4o’clock a.m., when we found ourselves completely surrounded, as far as the eye could reach from the maintop-gallant masthead, by icebergs of every size and form, varying from 50 tons to bergs of 150 feet in height, and half a quarter of a mile in length; they were carried by a current in a N.N.E. direction, we were obliged to vary our course continually while passing through them, and, the wind having fallen light, to aid the ship’s steering by often bracing round the yards. We were about 20 hours getting through them, and being providentially favoured with clear weather, in connection with the able exertions and coolness of Captain Durant, aided by the activity and promptness of the first and second officers (Messers Payne and Allen), and crew, we were enabled to get clear of them without any casualty; but had we met them in rough weather, or on a dark squally night, our chance of escape would have been problematical.”[7]

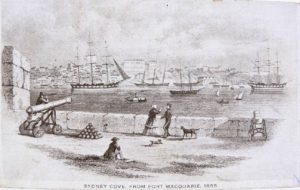

The Washington Irving arrived just outside of Sydney Cove. Despite signalling for a Harbour Pilot the Ship was not boarded by a Pilot until the Washington Irving was off Middle Head.[8] The Pilot who finally responded to the signals was called Hawkes.[9] Pilotage has been used in Sydney Harbour since the 1790’s. Pilotage is used to minimise accidents in the Harbour. Trained Pilots board a ship and take over direction of that ship until it is berthed. Pilots also take ships out of the Harbour when they are leaving Sydney.[10] Without a trained Pilot the entry to Sydney Harbour can be a very dangerous one. There are no safe places outside of the Harbour to anchor a ship while awaiting a Pilot. So the lack of response from the Pilots was dangerous to the ship and the people aboard.

A sepia toned postcard featuring an image of Sydney Cove, titled ” SYDNEY COVE, FROM FORT MACQUARIE, 1855″. Courtesy of the National Museum of Australia.

Once in port the trials for the Washington Irving were not over. Captain Isaac Durant neglected to have a watch on board his ship and was thus bought before the Water Police Court in April and fined 10 Shillings for this neglect.[11]

It was in Sydney that Edwin Gransden left the Washington Irving and its crew including Captain Durant.

[1] 1852 ‘Sydney News.’, The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser (NSW : 1843 – 1893), 29 December, p. 2. , viewed 19 Jun 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article658847

[2] Google Books. Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping. Cox and Wyman Printers 1857. Original from Harvard University. Digitized 4 Dec 2007. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RkASAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=editions:0Ftz6zT302-gFzEJxA5c6C&hl=en#v=onepage&q=felt&f=false (accessed 20 June 2016)

[3] 1855 ‘SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE.’, The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser (NSW : 1843 – 1893), 14 April, p. 3. , viewed 20 Jun 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article700129

[4] 1855 ‘NEWCASTLE.’, The Shipping Gazette and Sydney General Trade List (NSW : 1844 – 1860), 16 April, p. 75. , viewed 20 Jun 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article161108537

[5] 1855 ‘NEWCASTLE.’, The Shipping Gazette and Sydney General Trade List (NSW : 1844 – 1860), 16 April, p. 75. , viewed 20 Jun 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article161108537

[6] 1855 ‘NEWCASTLE.’, The Shipping Gazette and Sydney General Trade List (NSW : 1844 – 1860), 16 April, p. 75. , viewed 20 Jun 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article161108537

[7] 1855 ‘To the Editor of the Sydney Morning Herald.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 21 April, p. 4. , viewed 20 Jun 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12968384

[8] 1857 ‘The Sydney Morning Herald.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 14 November, p. 4. , viewed 20 Jun 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13002975

[9] 1857 ‘SHIP WASHINGTON IRVING.’,Empire (Sydney, NSW : 1850 – 1875), 23 November, p. 5. , viewed 20 Jun 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article60260775

[10] Dictionary of Sydney staff writer, Harbour pilots, Dictionary of Sydney, 2008, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/harbour_pilots, viewed 20 June 2016

[11] 1855 ‘WATER POLICE COURT.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 20 April, p. 4. , viewed 19 Jun 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12968368