100 years since the end of World War 1. It is time to write about a Gransden experience of War.

Lest We Forget!

Private Stimpson Alfred Gransden enlisted on the third of November 1915. Within months he had participated in the Battle of Pozieres and become a member of the 4th Machine Gun Company. In this position, he participated in the first Battle of Bullecourt where he was wounded and went missing. For the remainder of the First World War, Stimpson Gransden was moved from one Prisoner of War camp to the next.

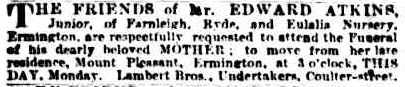

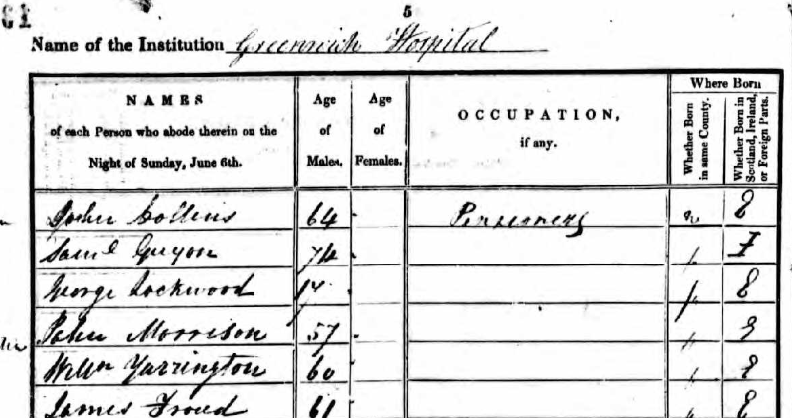

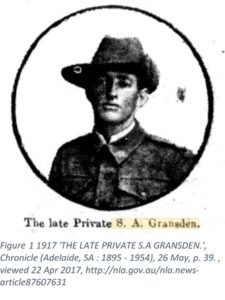

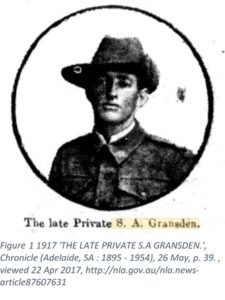

Private Stimpson Alfred Gransden No. 3830, 4th Australian Machine Gun Company, 4 Section, 4 Brigade, 4 Division, Late of the 27th Battalion went missing since the 11th of April 1917[i]. There were very few details in the telegram, just, “Reported missing since April 11th 1917”. It was enough that the local newspaper printed a photograph of Stimpson Gransden, captioned “The Late Private S. A. Gransden[ii]”.

Like many war-torn families, Louisa Gransden, mother to Stimpson Gransden, wrote to the Red Cross, asking them to help her to find her son[i]. Only a few days later Louisa received another telegram. Again Louisa unfolded a telegram to see the words “Reported Missing[ii]”. This telegram was to inform Louisa that her son Oliver Alfred Gransden had also gone missing on the 11th of April 1917[iii].

The Red Cross kept in touch and helped many hundreds of family members like Louisa Gransden. Their volunteers and workers wrote back to Louisa and her family to reassure them that they would search for both of her sons. They sent her commiserations on the loss of two soldiers during the war. They also let her know, that it would take many weeks before the German lists would show her sons names, searching would take time.[iv]

After almost two months Louisa finally heard back from the Red Cross. Both of her sons had been taken prisoner during the first Battle of Bullecourt. The telegram read;

“We are today in receipt of a cable from the Red Cross Commissioners stating the above soldier is a Prisoner of War in Lazarett Verden Aller, Germany, slightly wounded in the leg.

A few days ago we notified Mrs. Gransden that your other son, Private O.A. Gransden, 2165 of the 48th Bttln was also a Prisoner. We feel sure the knowledge that although your boys are prisoners in Germany, they are alive will comfort you a little”.[i]

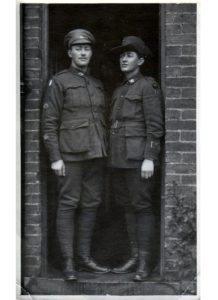

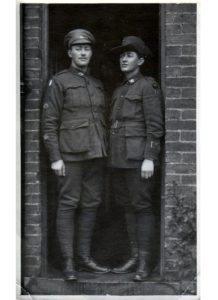

Many things had sent Louisa’s sons to war. The family lived on a farm in South Australia[ii]. It was not a well off-farm and both boys had little to look forward to other than a life of farm labouring. By joining up, both boys could look forward to adventures and would possibly get the opportunity to meet their cousins who lived in England. They would also gain skills and knowledge that may help them expand beyond the confines of the farm for work, once the war was over. After the elder boy, Stimpson had joined up, it was only a matter of time before the younger son, Oliver, also joined up. It was a source of happiness to both men, that within months of the younger man joining they had been able to spend a short time with their cousin, in Kent England, in between spells on the Continent at War[iii]. This was an experience that neither boy had ever thought they would be able to have, living, as they did, on a small farm in rural South Australia.

Oliver and Stimpson Gransden

When Stimpson had first joined the 27th Battalion, he had joined with a group of many young men from South Australia[iv]. It was not long before they were on their way to the Western Front. Stimpson joined the Battalion as a member of the 9th Reinforcements and like many others, his first experience of war was when he entered the front line trenches, for the first time on the 7th of April and later fought at the battle of Pozieres[v]. By November that year, Stimpson had moved to the 4th Australian Machine Gun Company[vi].

The next major conflict that Stimpson participated in was the Battle of Bullecourt. Stimpson was part of the 4th Australian Machine Gun Company. Stimpson and the other members of the 4th Australian moved forward at 4am. The Company experienced heavy machine gun fire almost immediately. Although the Company achieved their first and second objectives they were unable to hold their positions due to a strong counterattack and failing supplies. At 12.30pm the Company was forced to retire leaving behind the majority of their men, including Simpson Gransden and more than 100 others. Of the 4th Australian Machine Gun Company, in the first Battle of Bullecourt, just over 10% of men, officers and equipment made it back to their own lines[vii].

After the Battle of Bullecourt Stimpson and many of his fellow soldiers were officially classified as missing. The Redcross, during this time, spent many weeks looking for the Gransden men, and thousands of other soldiers who had gone missing, in this battle and in others. It took them almost three months to find Stimpson Gransden and others who had gone missing that day, including Stimpson’s brother Oliver Arthur Gransden of the 48th Infantry Battalion[viii]. The wait for news meant that many family members were both in mourning and still waiting for news of their loved ones. This was a difficult situation for families to be in, particularly as they had their own work to do at home. Louisa, in particular, was looking after an unwell husband and running the family farm.[ix]

Stimpson and his brother never saw battle again. They were moved from one Prisoner of War Camp to the next until the end of the War when they were repatriated back to England and then onto Australia. During this time Stimpson experience starvation, deprivation and mistreatment. He remained cheerful in the very few letters and postcards that he was allowed to write home, but he also made it clear that he was surviving on the Redcross parcels, that he was receiving, of food and clothes.[x]

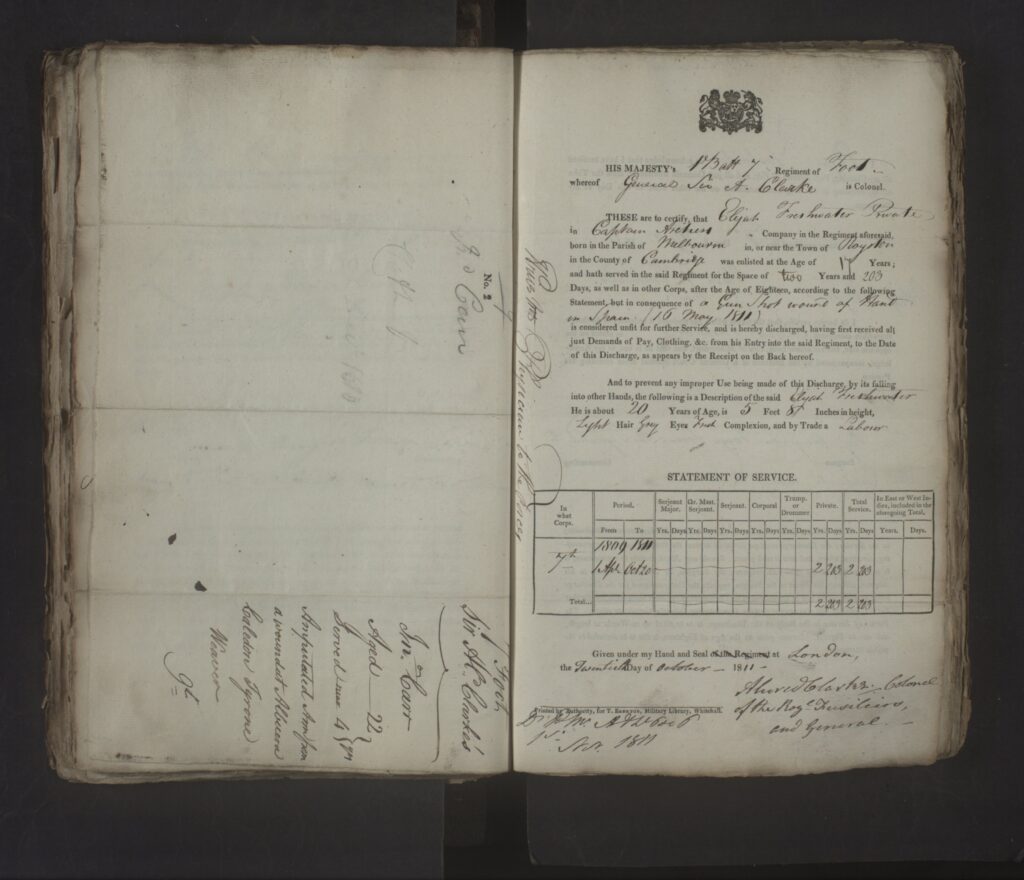

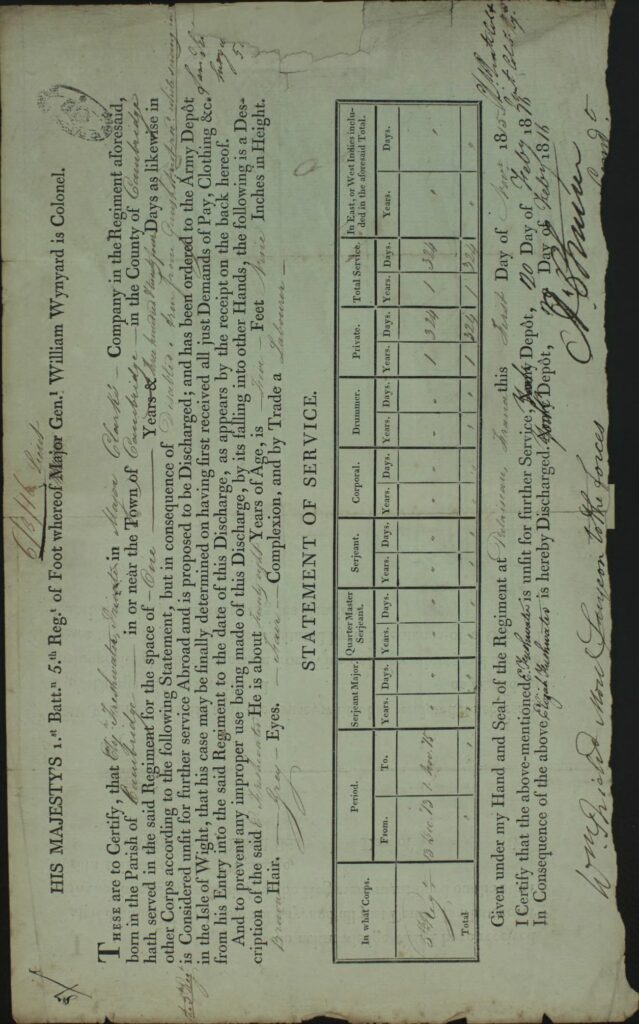

On the 17th of June 1919, Stimpson was discharged from a Hospital in Adelaide, South Australia. He had spent just 14 months in the trenches fighting against the Germans. The remainder of his three years and 283 days was spend as a Prisoner of War. Stimpson returned home to a hero’s welcome and a loving family. His time during the war had changed him, it had changed his family and the lives of everyone around him.

Stimpson and Agnes Gransden

[i] Ibid.

[ii] National Archives of Australia. Gransden Stimpson Alfred : SERN 3830 : POB Port Broughton SA : POE Adelaide SA : NOK M Gransden Louisa. https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=4669823 (Accessed 27th Apr 2017)

[iii] Authors Collection. 2003 Oral History, interview between Christina Bean and Kathleen Welch.

[iv] Australian War Memorial, 27th Infantry Battalion, awm.gov.au. https://www.awm.gov.au/unit/U56108/ (Accessed 27th April 2017)

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Opcit National Archives of Australia. Gransden Stimpson Alfred : SERN 3830 : POB Port Broughton SA : POE Adelaide SA : NOK M Gransden Louisa. https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=4669823 (Accessed 27th Apr 2017)

[vii] Australian War Memorial, AWM4 24/9/10- April 1917. RGDIG1007720. https://www.awm.gov.au/images/collection/bundled/RCDIG1007720.pdf (Accessed 28th Apr 2017)

[viii] Opcit South Australian Red Cross Information Bureau 1916-1919. Ref SRG 76/1/2453.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Opcit South Australian Red Cross Information Bureau 1916-1919. Ref SRG 76/1/2375

Bibliography

1917 ‘THE LATE PRIVATE S.A GRANSDEN.’, Chronicle (Adelaide, SA : 1895 – 1954), 26 May, p. 39. , viewed 22 Apr 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article87607631

Australian War Memorial, AWM4 24/9/10- April 1917. RGDIG1007720. https://www.awm.gov.au/images/collection/bundled/RCDIG1007720.pdf (Accessed 28th Apr 2017)

Australian War Memorial, 27th Infantry Battalion, awm.gov.au. https://www.awm.gov.au/unit/U56108/ (Accessed 27th April 2017)

Authors Collection. 2003 Oral History, interview between Christina Bean and Kathleen Welch.

National Archives of Australia. Gransden Stimpson Alfred : SERN 3830 : POB Port Broughton SA : POE Adelaide SA : NOK M Gransden Louisa. https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=4669823 (Accessed 27th Apr 2017)

South Australia Library (SLA). South Australian Red Cross Information Bureau 1916-1919. Ref SRG 76/1/2453. Packet Number. 2453 Private 2165 48th Infantry Battalion https://sarcib.ww1.collections.slsa.sa.gov.au/soldier/oliver-arthur-gransden

South Australia Library (SLA). South Australian Red Cross Information Bureau 1916-1919. Ref SRG 76/1/2375. Packet Number. 2375 Private 3830 27th Infantry Battalion. Viewed 23 Apr 2017 https://sarcib.ww1.collections.slsa.sa.gov.au/soldier/stimpson-alfred-gransden

[i] Opcit. SLA. Ref SRG 76/1/2375.

[ii] South Australia Library (SLA). South Australian Red Cross Information Bureau 1916-1919. Ref SRG 76/1/2453. Packet Number. 2453 Private 2165 48th Infantry Battalion https://sarcib.ww1.collections.slsa.sa.gov.au/soldier/oliver-arthur-gransden

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Opcit SLA. Ref SRG 76/1/2375.

[i] South Australia Library (SLA). South Australian Red Cross Information Bureau 1916-1919. Ref SRG 76/1/2375. Packet Number. 2375 Private 3830 27th Infantry Battalion. Viewed 23 Apr 2017 https://sarcib.ww1.collections.slsa.sa.gov.au/soldier/stimpson-alfred-gransden

[ii] 1917 ‘THE LATE PRIVATE S.A GRANSDEN.’, Chronicle (Adelaide, SA : 1895 – 1954), 26 May, p. 39. , viewed 22 Apr 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article87607631